As I write this, record rainfall has led to mass evacuations and mass casualties in Guizhou province in China, where upwards of 80,000 have been evacuated, in northeast India, where at least 44 died from flooding and landslides, and in Texas in the United States, where the Guadalupe River rose 26 feet in a mere 45 minutes, resulting in more than a hundred deaths. Only weeks earlier, much of the Eastern US was being boiled in a humid heat dome so extreme that at least three workers died when “wet bulb” temperatures were exceeded. Between early March and late June, cases of heatstroke skyrocketed across India, with at least 14 confirmed deaths (the true number likely being an order of magnitude higher). In eastern China, the subtropical “sanfu season,” when heat peaks in the summer, has started earlier and earlier, taxing the power grid.

Nor are these “natural” disasters, in any sense. In China’s southwest, flash-flooding has been aggravated by the rapid development of built space, as construction projects in the mountainous interior uproot vegetation and encase drainage areas in cement. In the US, the disasters are better described as a catastrophic form of developmental decay, as rotting infrastructure and severe cuts to federal emergency and atmospheric monitoring agencies were in part to blame for the death toll in Texas and similar catastrophes in earlier hurricane and fire seasons. In all cases, however, the “natural” character of these disasters is called into question by their obvious links to anthropogenic climate change. For this reason, many are also the consequence of an inability or unwillingness to adapt our infrastructure to an increasingly uninhabitable world. For example, in Europe, as in India, a lack of widespread air conditioning infrastructure ensures that extreme heat brings a wave of deaths each year: as many as 175,000 annually.

Meanwhile, the long-running but spasmodic transformation of global trade networks had seen steady inflation in asset prices alongside added volatility in the cost of basic goods as tariffs were threatened, scrapped, and reimposed according to political whim. Already strained supply chains began to shatter. As a result, deflationary conditions in China have produced a sustained employment crisis while inflationary conditions elsewhere have led to the worst cost-of-living crisis in a generation, spanning poor and rich countries alike. Geopolitics has, quite literally, become a bread-and-butter issue across much of the globe, as hundreds of millions of young people watch a livestreamed genocide and see in it not simply our increasingly callous world but also their own immediate future, backlit by drone swarms and the sudden light of bombs dropping on fields of twisted steel. Whether ecological, economic, or political, it appears that the “planetary” is now, in every sense, immediate.

This new reality was conceptualized earliest within the natural sciences, which introduced terms such as “anthropocene” into common parlance. In the same register, geomorphologist Robert K. Haff proposed the term “technosphere” to describe “the interlinked set of communication, transportation, bureaucratic and other systems that act to metabolize fossil fuels and other energy resources.” Now operating at the scale of a geospheric system, the sum of human technology could thereby be viewed “as a geological phenomenon” that “exhibits large-scale appropriation of mass and energy resources, shows a tendency to co-opt for its own use information produced by the environment, and is autonomous.”[1] As a result, according to Haff, “humans have become entrained within the matrix of technology and are now borne along by … supervening dynamics from which they cannot simultaneously escape and survive.”[2] And the bulk of these technologies are industrial in character, visible in the simultaneous expansion of gargantuan biological infrastructures (monocultures, factory farms, tree plantations, parks and forest reserves, etc.) and the enormous mass of abiotic material pulsing between the continents at any given moment and deposited in layered strata of technical installations (plant and equipment, transport networks, housing complexes, mega-dams and mega-ports, etc.) to form an exoskeleton of concrete and steel wrapped around the globe.

Glittering constellations of urban space, megalithic mines gouged out of mountaintops, oceans of shivering grain, denuded glaciers slick with melt pools, forests burning orange against the sky—all are elements of a “new nature” sculpted not by technology or even a generic “humanity” but by the specific imperatives of capitalist society.

While it might at first seem as if this geospheric system is driven by the quasi-autonomous, essentially thermodynamic “agency” of this technical exoskeleton (as Haff himself claims), what Haff calls the “technosphere” is better understood as a new planetary geography accreted through the continual motion of distinctly social forces across the surface of the Earth. Glittering constellations of urban space, megalithic mines gouged out of mountaintops, oceans of shivering grain, denuded glaciers slick with melt pools, forests burning orange against the sky—all are elements of a “new nature” sculpted not by technology or even a generic “humanity” but by the specific imperatives of capitalist society. It is less “technology” and more “technics,” in the sense used by Lewis Mumford, for whom technical invention ultimately served social imperatives:

To understand the dominating role played by technics in modern civilization, one must explore in detail the preliminary period of ideological and social preparation. Not merely must one explain the existence of the new mechanical instruments: one must explain the culture that was ready to use them and profit by them so extensively.[3]

As described by Jason W. Moore: “For Mumford, power and production in capitalism embodied and reproduced a vast cultural-symbolic repertoire that was cause, condition, and consequence of modernity’s specific form of technical advance.”[4]

It is in this sense that the urban geographers Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid, drawing from Henri Lefebvre, refer to a process of “planetary urbanization,” in which deagrarianization and urban concentration have proceeded to a critical point beyond which “a complete urbanization” is achieved, in which even ostensibly “rural” areas become “technical lands” serving urban needs. This complete urbanization thereby becomes

a basic parameter for planetary social and environmental relations, imposing new constraints upon the use and transformation of the worldwide built environment, unleashing potentially catastrophic inequalities, conflicts and dangers, but also harboring new opportunities for the democratic appropriation and self-management of space at all scales.[5]

Martín Arboleda describes the concept in further detail:

As opposed to the “spaces of flows” and “liquid modernities” that populated earlier visions of globalization, the notion of the planetary designates a convoluted terrain where fences, walls, and militarized borders coexist with sprawling supply chains and complex infrastructures of connectivity. This realm is traversed by deeply contradictory and yet complementary tendencies toward advanced functional integration in the world economy and toward radical ethnoracial and sociospatial fragmentation.[6]

As a result, Arboleda is able to treat both the extractive sector and specific extractive sites as embodiments of a “planetary mine” which itself functions as a key moment in the metabolism of capitalist society, now operating at the geospheric scale.

If the “planetary mine” captures the extractive character of “planetary urbanization,” literally etched into the crust of the Earth via the removal of mass (individual mines understood as “inverted cities”), the concept of a “planetary factory” deployed this project is intended to invoke the same process in its positive dimension, tracing how this mass is transmuted and redistributed across the Earth’s crust by human labor to form a distinctively capitalist material culture visible both in the flurry of consumer commodities swarming across the surface of the globe at any given moment and in the slower accretion of new physical geographies in an ongoing cycle of implantation, demolition, and reconstruction.[7] Vast reproductive infrastructures are also necessary for such spaces to sustain life (i.e., gargantuan housing complexes, continent-spanning power grids, advanced water and waste systems, and of course armies of reproductive laborers, paid and unpaid), and the planetary factory can therefore be categorized as lying within a more encompassing “planetary social factory.”[8]

At the same time, however, stressing that the productive world relies on a reproductive base is, in fact, backward. The geography of social reproduction is subordinate to the geography of value, visible in the spatial structure of the productive sphere. Within capitalist society, then, reproductive functions are made ancillary to the imperatives of accumulation and therefore develop as second-order accretions around what economic geographers Michael Storper and Richard Walker refer to as the “territorial industrial complex,” broadly defined as “an extensive work site that brings disparate production activities into advantageous relation with each other, at a larger scale and scope than the individual workplace, firm, or even, in many cases, the industry,” and can operate at multiple spatial scales, including that of the “metropolis” as a whole, the “regional complex” or “manufacturing belt,” a “city-satellite system” or even a “cluster of towns.”[9] We can understand the territorial industrial complex as a spatial node or even organ in the larger metabolism of capitalist society. Physical mass extracted from Arboleda’s “planetary mine” and human labor (historically from the rural periphery but increasingly from less competitive urban territories subject to continual outmigration and thereby rendered into “rust belts”) are siphoned into this node, and transmuted physical artifacts are spit out of it.

The planetary factory is therefore visible in the concrete form of urban technical infrastructure built up in service of the market. But it is also visible, in the “cadastralization” of both physical and social space, through which territory is cut up into non-overlapping plots of property (cadasters), each with a clearly designated owner. Though abstract, the cadaster is just as visible as the spread of urban space itself. Take, for example, the satellite photograph used as the avatar for this page:

[Source]

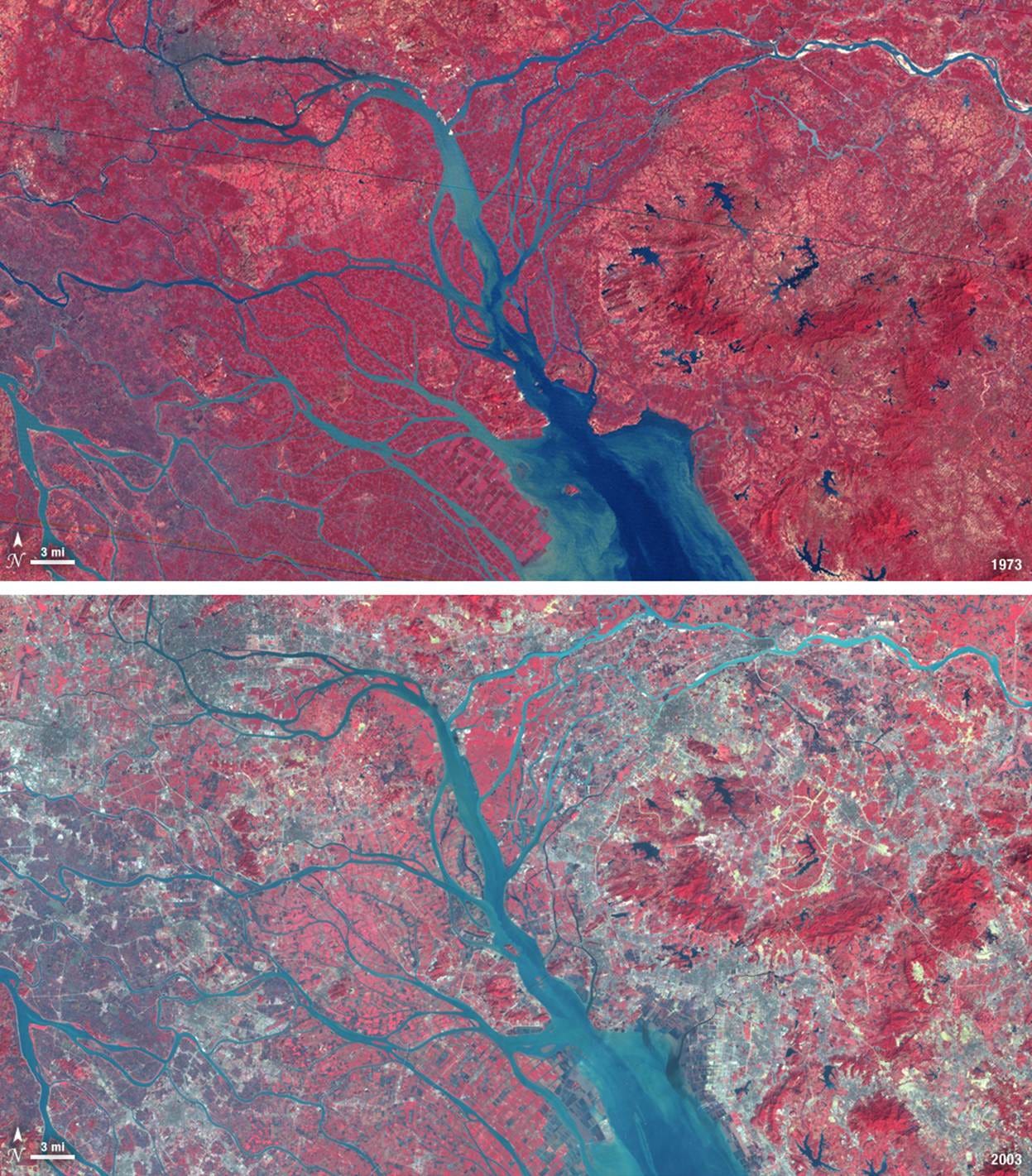

The image is a slightly modified version of a near infrared photograph taken of the Pearl River Delta in China by Landsat in 1995. Since vegetation is easily captured in infrared, timelapses of satellite images such as this are often used to track and quantify urbanization. Here is another example of the same region, comparing 1973 to 2003:

[Source]

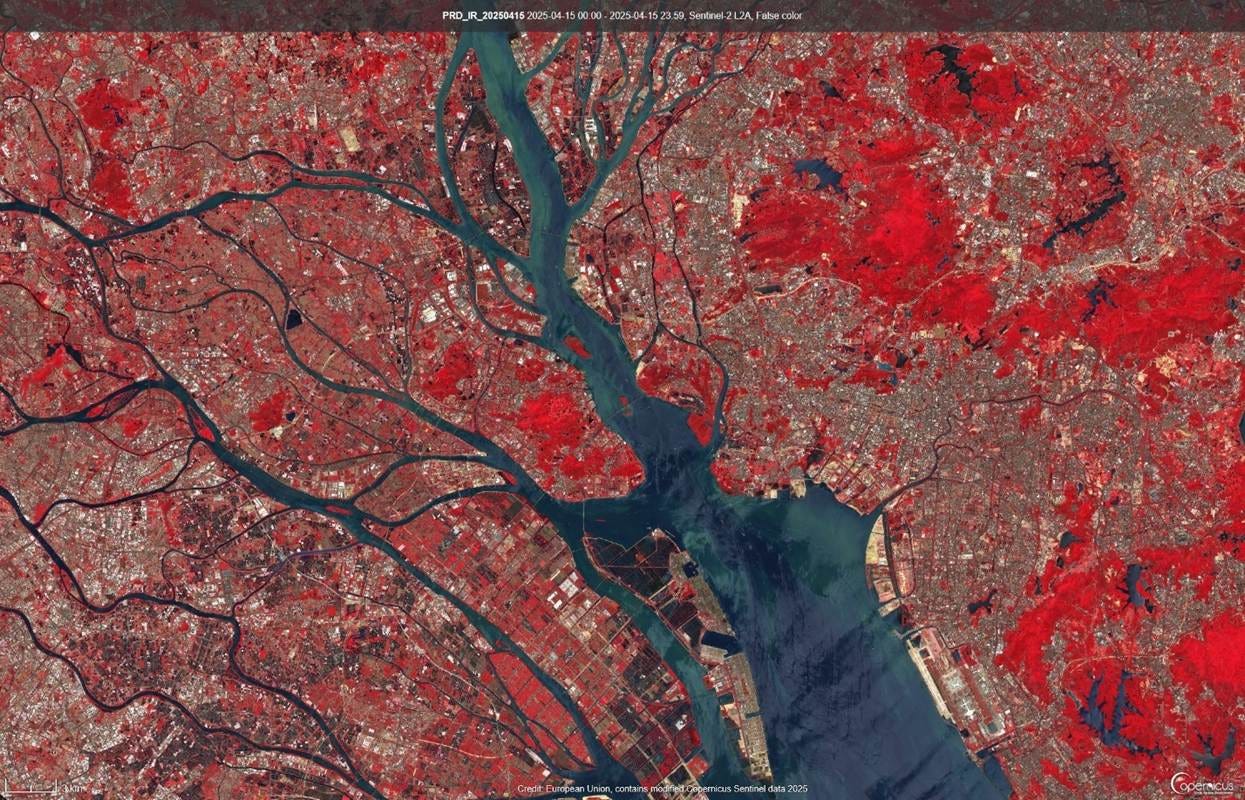

In addition to showing the displacement of vegetation by concrete and steel, such images also illustrate the cadastralization of space insofar as the geometric grids that emerge through the development process simultaneously express social divisions. Though they are social abstractions expressing a certain form of ownership, cadasters are often quite literally visible in the plotting of land and thereby become a feature of physical geography. For example, the same area zoomed in slightly, viewed in April of 2025 (captured by Sentinel-2), clearly illustrates an extensive cadastral system that encompasses built space, vegetation, and even aquatic territory along the river:

[Source]

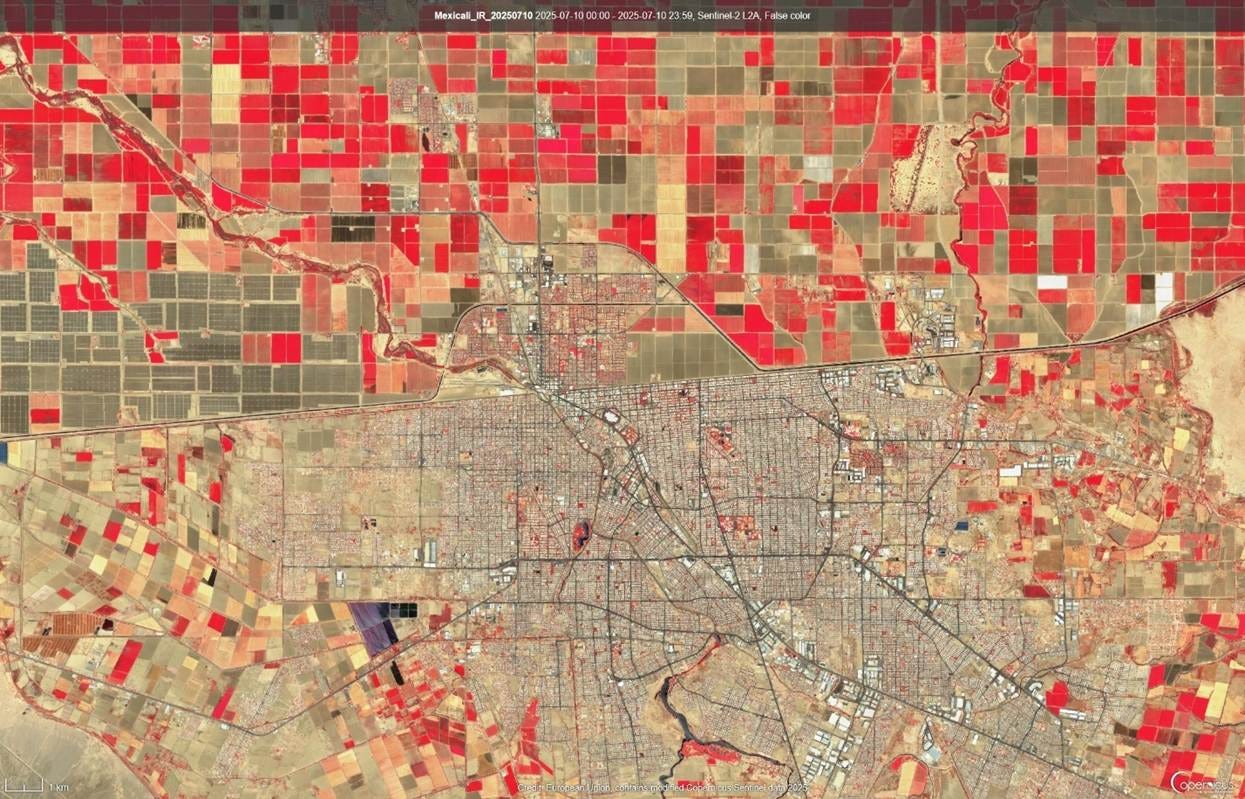

Similarly, even larger-scale geopolitical divides are often visible in these raw images of vegetation and developed space. Here, for example, is the US-Mexico border separating Calexico from Mexicali, photographed in July of 2025:

[Source]

And, on the final frontiers of commodity society, where the market is now extending into territories that once lay on periphery of global capitalism—and have now been fully subsumed within it, functioning as hinterlands rather than peripheries—the deepening of these social relationships is literally visible in the gradual emergence of this cadastral grid from areas that once appeared as tangling jungles or sand-swept stretches of desert. Here, for example, is a rural corner of the Southeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (in Tanganyika Province, just east of Lake Tanganyika, just north of Lake Mweru Wantipa and the border with Zambia), where market relations are advancing through an expanding constellation of artisanal mines and affiliated cash-cropping, also photographed in July of 2025:

[Source]

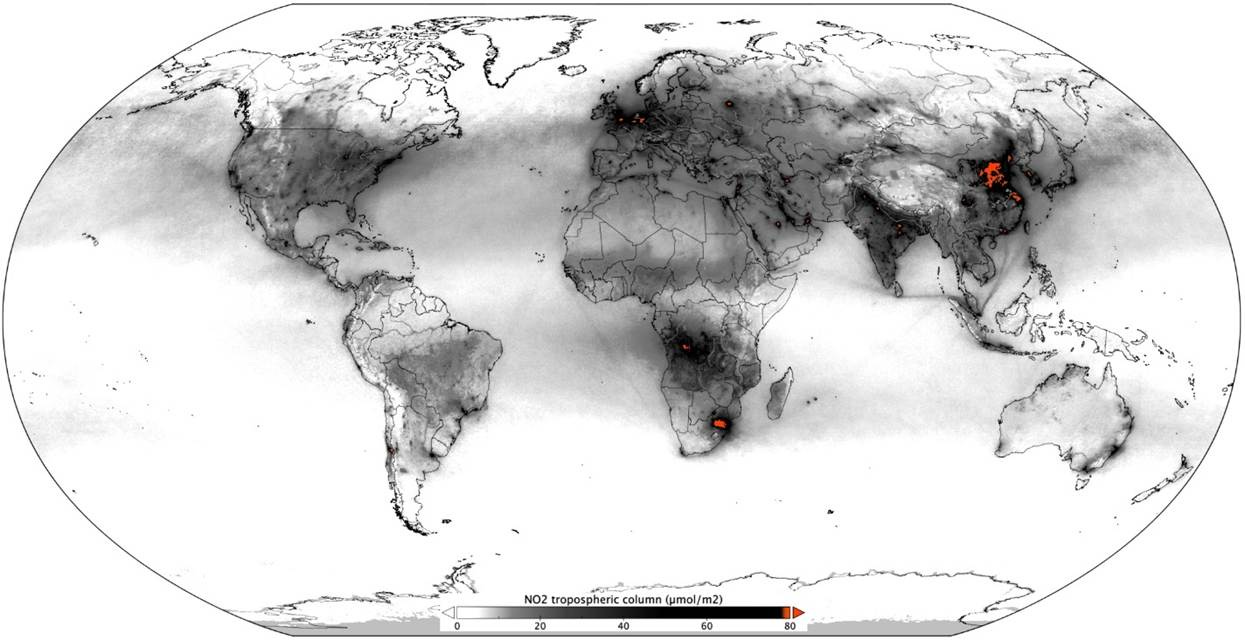

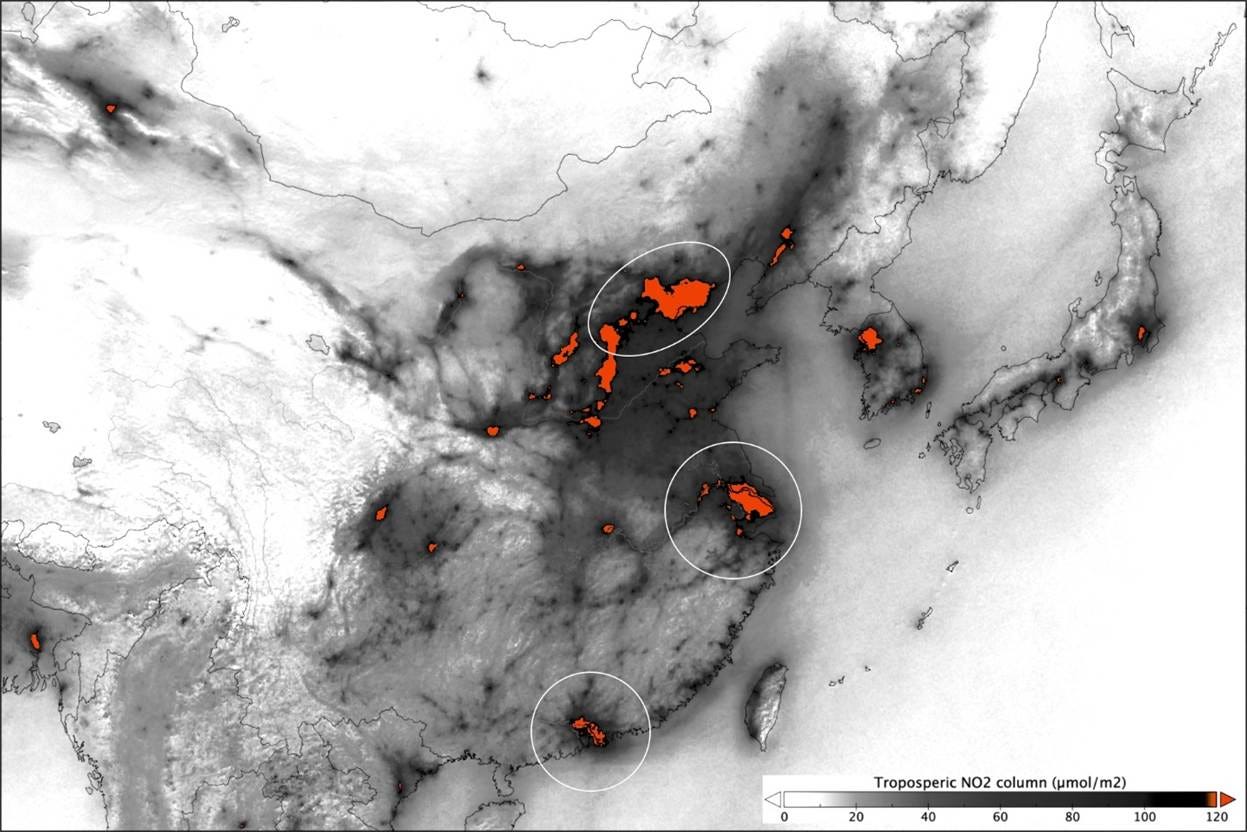

As a whole, however, the planetary factory is perhaps best captured not in static images of its “technical exoskeleton” or even in the social grid-structures that scaffold this carapace but instead in the dynamic, energetic image visible in measures of nitrous dioxide (NO2) emissions. Though NO2 only accounts for a relatively small share of global greenhouse gas emissions, remote sensing of NO2 is able to capture a relatively immediate picture of human industrial activity and, in particular, visualizes the agroecological dimension of this activity via emissions from things like fertilized soil, crop residue burning, and deforestation. Perhaps the most concise image of the “planetary factory” is therefore something like this image of global average NO2 emissions from 2018, as captured by the Snetinel-5P satellite:

[Source, color scheme simplified]

On this map, NO2 appears in the form of dark clouds, colored red at the highest concentrations.[10] Trade routes are literally visible in this cloud, including narrow stretches of container shipping across the oceans. Though the densest concentrations are around urban areas, agricultural zones are also visible, as across much of the continental US. The map also shows the ongoing deforestation in Central Africa and clusters of coal-burning and crop-burning in places like South Africa, across India, and in the Chinese central plain. But the most distinct feature of the map is perhaps its concrete depiction of all the central nodes of global industry, visible in China’s megacities:

[Source, color scheme simplified, circles added]

Circled on the map here are the Pearl River Delta megacity, the Yangtze River Delta megacity, and the Jin-Jing-Ji megacity, the latter extending southwest into the newer urban complex stretching from Shijiazhuang south to Zhengzhou. Other established urban nodes are equally visible: Chongqing, Chengdu, Wuhan, and Xi’an in China (not to mention coal-burning clusters in Shanxi and in the Anshan area), as well as Seoul and Tokyo. The emerging industrial complex in Vietnam’s Red River Delta is also evident, though far lighter.

Although these physical signals track the raw expansion of society’s technical exoskeleton, however, they fail to capture the conflictual social forces driving it. At the macroscopic scale, these forces can only be documented through the abstraction of high-level analysis (as the “social logic” of capital or simply the “laws of motion” of capitalist society). Greig Charnock and Guido Starosta, both associated with the Centro para la Investigación como Crítica Práctica (CICP), offer a useful summary along these lines:

In its general determination as self-valorising value, capital is actually a materialized social relation between commodity owners differentiated into social classes, which, in its fully developed form as the total social capital, becomes inverted into the (alienated) subject of the unity of the process of social reproduction and its expansion.[11]

What can be described as the planetary factory is therefore not simply a system of material flows or interlocked corporate supply chains but instead the materialization of this social relation, including its class character.

Beyond this, however, the social forces driving forward this “alienated subject” are best illustrated in granular detail, via the “conjunctural” analysis of class conflict treated as a living expression of a particular history, in a particular territory, and expressing a particular confluence of productive and reproductive activities within the global division of labor. As political moments, these conjunctures must also be understood in their subjective dimension: as the expression of a collective political consciousness. Articulated in the moment through action and elaborated after-the-fact in the aesthetics, theories, and organizational disposition of participants, this mass subjectivity is stuttering and often indistinct. But its political force is self-evident. Ultimately, this subjective dimension is not reducible to the structural features of the planetary factory. And yet subject emerges from structure, implying that there must, ultimately, be some relation between the two. Loosely, we can think of the planetary factory as constraining the field of probable political expressions (and thereby the most likely forms of political subjectivity) by conditioning the “productive subjectivity” of the collective worker, visible in the intricate technical subdivision an uneven geographic distribution of both abstract scientific knowledge and practical experience in production.

All these features of the planetary factory are explored in detail in my book Hellworld: The Human Species and the Planetary Factory, out now in the Historical Materialism Series.[12] The project follows from my earlier book, Hinterland, which focused on the changing political and industrial geography of the US. I’m now launching this blog to promote the new book and to annotate my ongoing research process. I will be using it to post a wide range of content, including field notes, data analysis, literature reviews, early drafts of papers, advance copies of book chapters and forthcoming articles, alongside various archival ephemera. In addition to promoting the books and other work, this project will allow me to gather my own bibliography together in one convenient location and, I hope, provide at least a trickle of funding to subsidize this research, allowing me to spend less time in the menial labor or poverty-wage adjunct positions that I currently rely on to survive in the absence of a more stable job.

The themes and topics addressed in any given month will vary widely. One important thread will be an ongoing series that returns to industrial and demographic trends in the US, exploring the role of international capital (and in particular firms from across Asia) in the so-called “reindustrialization” of the US South. Another theme will be an exploration of the question of political subjectivity, picking up where Hellworld left off in preparation for a future book project (not nearly as long, I promise) on the “question of organization.” But much of the content will simply be incidental: whatever I happen to be working on that week, old fragments pulled from the archive, some interesting data I came across. Since part of the point is to make money, we’ll simply have to see what sells.

[1] P.K. Haff, “Technology as a geological phenomenon: implications for human well-being”, in Waters, C. N., Zalasiewicz, J. A., Williams, M., Ellis, M. A. & Snelling, A. M. (eds), A Stratigraphical

Basis for the Anthropocene, Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 395. p. 1

[2] ibid, p.2

[3] Lews Mumford, Technics and Civilizaiton, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1934. p.4

[4] Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital, New York: Verso, 2016. p.176

[5] Neil Brenner, “Introduction: Urban Theory Without an Outside”, in Neil Brenner (Ed.), Implosions / Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, .p. 18

[6] Martín Arboleda, Planetary Mine: Territories of Extraction under Late Capitalism, New York: Verso, 2020. pp.15-16

[7] The concept is developed more thoroughly in my book, Hellworld: The Human Species and the Planetary Factory.

[8] The term is used by Alessandra Mezzadri in “Life and the Labour Process in the Planetary Social Factory”, Global Labour Journal, 16(2), May 2025. <https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v16i2.6723>

[9] Michael Storper, Richard Walker, The Capitalist Imperative: Territory, Technology, and Industrial Growth, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989. pp.139, 141

[10] This and the following map are slightly modified versions of two figures used in Chapter 2 of my book, Hellworld: The Human Species and the Planetary Factory.

[11] Greig Charnock and Guido Starosta, “Introduction: The New International Division of Labour and the Critique of Political Economy Today”, in Charnock and Starosta (Eds.), The New International Division of Labour: Global Transformation and Uneven Development, 2016, p.5

[12] Books in the HM Series are first published in expensive “library editions” via Brill and, one year later, a retail paperback is released by Haymarket. At the time of writing, only the expensive library edition is available for sale, including a pdf that can be accessed via most universities. The actual retail edition should be released sometime in the summer of 2026.